|

Multiple shear bands can primarily be characterized by the number of sets that they contain and their intersection angles. Shear band systems comprising two sets are the most common (Davis et. al., 2000) which are generally referred to as conjugate fault sets. In fact, the closest approximation found in nature to an ideal conjugate set of faults are complementary sets of shear bands with normal (Figure 1), strike-slip (Figure 2 and Figure 3), and reverse/thrust (Figure 4 and Figure 5) sense of displacements. The smaller intersection angles between the shear bands in the field varies from about 20 degrees to about 45 degrees as seen in the photographs and maps provided here. Recent experimental studies indicate that the failure angle depends on the mean stress as well as the orientation and magnitude of the Principal Stresses (see, for example, Ma and Haimson, 2016). The nature of the intersections of the Riedel Shear sets provide the age relationships between them as well as their progressive rotations (Katz et al., 2004). These results indicate that the meaning and significance of intersection angles of shear bands are complex issues and should be handled with care.

| | Figure 1. Conjugate shear bands with normal sense of shearing and about 35 degree intersection angle in Entrada Sandstone exposed in the San Rafael Desert, southeastern Utah. From Aydin (1977). |

| | Figure 2. Two sets of shear bands with right-and left-lateral strike-slip sense of offset on a Navajo Sandstone pavement exposed at the Iron Wash, San Rafael Desert, Utah. From Aydin (1977). |

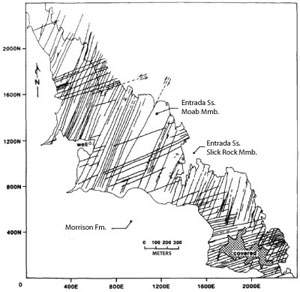

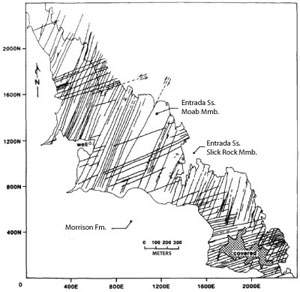

| | Figure 3. Map showing two sets of highly regular conjugate shear bands with right-lateral (N30E) and left-lateral (N60E) slip in the Jurassic Entrada Sandstone exposed in the Garden area on the SW limb of the Salt Valley Anticline near Arches National Park, Utah. The intersection angle varies slightly from one part to another, but is about 30 degrees on average. From Zhao and Johnson (1992). |

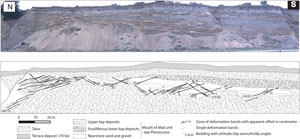

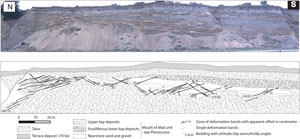

| | Figure 4. Photograph and map showing two major sets of shear bands with reverse or thrust sense of slip in poorly consolidated Pleistocene terrace deposits, McKinleyville, northern California. Also observed at the same locality are dilation and compaction bands at an angle to the dominant shear bands of thrust types. From Du Bernard et al. (2002; and Eichubbl et al. (2003). |

| | Figure 5. Conjugate thrust shear bands in poorly consolidated detrital deposits of late Pleistocene age exposed in the 83 ka Savage Creek marine terrace near McKinleyville, northern California. Photograph by X. du Bernard. |

More than two sets of shear bands also occur in nature. Four sets of shear bands with dip-slip sense have been described in the field and experiments (see, for example, 'Multiple Sets of Normal Faults'). These have well-defined orthorhombic symmetry and are attributed to 3-D strain fields.

| |

Aydin, A., 1977. Faulting in sandstone. Ph.D thesis, Stanford University, 246 p.

Aydin, A., Reches, Z., 1982. The number and orientation of fault sets in the field and in laboratory. Geology 10: 107-112.

Davis, G.H., Bump, A.P., García, P.E., Ahlgren, S.G., 2000. Conjugate Riedel deformation band shear zones. Journal of Structural Geology 22: 169–190.

Du Bernard, X., Eichhubl, P., Aydin, A., 2002. Dilation bands: a new form of localized failure in granular media. Geophysical Research Letters 29 (24): 2176 doi: 1029/2002GLO15966.

Eichhubl, P., Muller, J.R., Aydin, A., . The Stanford Rock Fracture Project 2003 Field Trip Guide. Stanford Digital Repository. Available at: http://purl.stanford.edu/bf848yf4530.

Katz, Y., Weinberger, R., Aydin, A., 2004. Geometry and kinematic evolution of Riedel shear structures, Capitol Reef National Park, Utah. Journal of Structural Geology 26: 491–501.

Ma, X., Haimson, B.C., 2016. Failure characteristics of two porous sandstones subjected to true triaxial stresses. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth.121, 6477-6499, doi:10.1002/2016JB012979.

Riedel, W., 1929. Zur mechanik geologischer Bruc-herscheinungen. Zentralblatt fuer Minera-logie, Geologie und Palaeontologie 1929B: 354-368.

Zhao, G., Johnson, A.M., 1992. Sequential of deformation recorded in joints and faults, Arches National Park, Utah. Journal of Structural Geology 14 (2), 225-236.

|